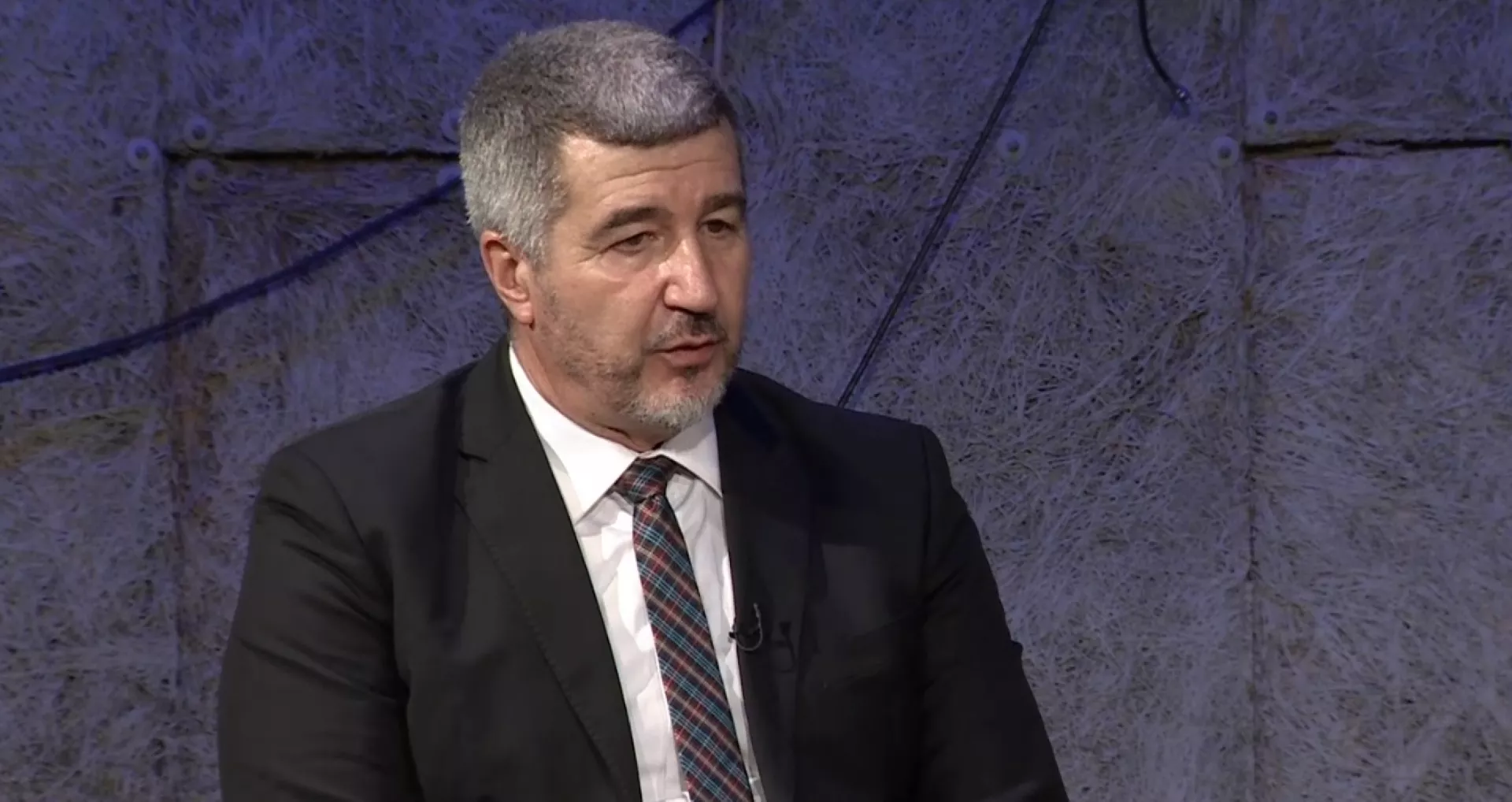

By: Armin Aljovic

French philosopher, journalist and filmmaker Bernard-Henri Lévy is one of the most influential and most prominent intellectuals of our time.

He is a fierce and tireless critic of politicians and different social phenomena, the nationalism and populism in particular, provoking reactions all over the world. He was heavily involved in campaigning for peace during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the nineties.

Today, with equal passion Lévy makes a plea for saving Europe ahead of the European Parliament elections on 23 May.

On the eve of his theater play 'Looking for Europe' in Sarajevo on 13 May, in an interview for BH news agency Patria, Lévy spoke about the reactions he provoked by calling Milorad Dodik, the Chairman of BiH Presidency – 'Putin's puppet', about destiny of Bosnia should the right-wing win in Europe. He also reveals how Sarajevo has become an eternal inspiration for a French philosopher...

While Sarajevo awaits your theater performance 'Looking for Europe' scheduled for next Monday at the National Theater Sarajevo, media attacks on you keep coming from the office of Milorad Dodik. You recently referred to him as 'populist' and 'one of Putin's puppets'. How do you feel about those attacks?

- I feel that they confirm my thesis. Which is that between the liberals and the illiberals stands Sarajevo, just as it did before. The fact that it’s Dodik’s people who are attacking me, and that they’re doing it so shamelessly, confirms that there are two camps in Europe. And that, between the two camps, the border continues to be defined by the question of Sarajevo. I’m not the problem. The problem is that someone like Dodik is sitting in the chair of Alija Izetbegović. That is a sacrilege, blasphemous to the spirit of Bosnia and immeasurably sad. I know that Mr. Dodik hates Sarajevo so much that he won’t come to the city, choosing instead to perform his presidential functions by videoconference. But that doesn’t matter. The symbol is there.

Your famous 'Manifesto to Save Europe' and your play 'Looking for Europe' warn of possible consequences of populism for the entire continent. Could Bosnia and Herzegovina be the ultimate consequence of the growing populism in Europe? You once stood against division of Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, its division is still on some agendas as it was in the nineties.

- Twenty-five years ago I was up in arms against everything that is happening now. The idiocy of the Dayton Accords. The shame of the peace agreement that blessed the division of the country. A Bosnia-Herzegovina that was not only sacrificed, but pulled apart as well. And the war aims of the Serbs achieved, despite their military defeat. That’s what the Dayton Accords formalized. And that’s what has reappeared today. You are indeed right to observe that populism is winning in Bosnia, which had been a model of coexistence and democracy. It was liberalism expressed as a country. Today, the pendulum is swinging in the other direction, and even Bosnia may be becoming a paragon of the illiberal drift.

Dodik's advisor, the film director Emir Kusturica, has accused you of recording war scenes in France and presenting them as images of Sarajevo under the siege... However, the citizens of Sarajevo could remember you coming to war-stricken Sarajevo a dozen times, your first visit taking place in those most difficult days of June 1992... How would you like to respond to his allegations?

- What response would be adequate in the face of such slanderous idiocy? You’re quite right to note that the residents of Sarajevo are well aware of the truth. They saw me during the war. They know that I was one of them and remain so. They know that I am one of those—one of the many, in fact—who sided with them during the Serbs’ war of aggression against Sarajevo. So, how should I respond to such a load of nonsense? The real problem is between Kusturica and Kusturica. The problem is the terrible drift of a man who was a real artist and became a guard dog for illiberalism and Putinism. It’s a very sad thing to see. There are other examples in the history of literature and film. But this particular example, the example of Kusturica’s slide and his conversion into the slave of a dictator and of dictators in general, is the most spectacular case of which I am aware. But Kusturica’s problem is not of the slightest importance to me personally.

You dedicated a great deal of your time and energy during Bosnian war - calling for peace. You remain committed to postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina. You recently stated that you would move some institutions from Brussels to Sarajevo, referring to its legacy of European civilization and multiethnicity. However, radical nationalists are after you because of Sarajevo. Isn’t that right?

- Yes, indeed. That’s how things are. It’s true that people hold Sarajevo against me. And it’s also true that Sarajevo is a wound in my side that won’t ever heal. As I say, that’s just how things are. People reproach me for Sarajevo, and I can’t forget Sarajevo. I see it as a symbol and an example. And that is something for which I’m not forgiven in Europe. Or, apparently, in Pale. I repeat, this is how things are. And it only serves to reinforce my thinking. It is true that my play ends as you say, that is, with an exhortation to instill a little of Sarajevo, a little bit of Bosnia, in each of the ailing European institutions. And with an exhortation to move the European Commission itself to Sarajevo. It’s a provocation, of course, but that’s not all it is.

Sarajevo – an inspiration to a world-renowned philosopher and a nightmare for many politicians in Bosnia and Herzegovina (and elsewhere). Your comment, please.

- Same comment, my friends! Between the philosopher that I am and the politicians to whom you refer there lies an abyss. And that abyss has the shape of the great little city of Sarajevo and the great little country of Bosnia. So, it’s indeed for the same reasons that I sing Sarajevo’s praises and that the ultra-nationalists, the bad shepherds of Bosnia, the corrupt politicians on Putin’s payroll, detest the city. Let’s not lose sight of the fact that Dodik, who happens to be the current president of Bosnia under the country’s institutional arrangements, is someone who hates Bosnia and has never pretended otherwise, a state of affairs that speaks volumes about the absurd Dayton process. I felt that absurdity right from the start. I recall Alija Izetbegović phoning me from his room in Dayton to tell me that the accord was bad but that he was going to be obliged to sign it. I remember him saying, and I quote, that he had a gun to his head and that Richard Holbrooke was the one holding it. Well, he was right. He knew that one day things would work out just as they have. He knew that Dayton meant the possibility of a Dodik running Bosnia, sitting in his chair, in his office, the same office in which the tears of Bosnia-Herzegovina under attack were shed.

What is your impression, from the time distance of 25 years, whether people in Bosnia and Herzegovina are aware of what you did for them during but also after the war? Yourself as well as some other voices of French intellectual elite such as Pascal Bruckner, Andre Glucksmann, Francis Bueb, etc.

- I really don’t know. We’ll find out on Monday. We’ll see who shows up at the National Theater of Sarajevo. We’ll see if anybody shows up! I hope that the younger generations appreciate the sacrifices that their mothers and fathers made. And I hope they know that their mothers and fathers had brothers and sisters in sacrifice. And that Glucksmann, Bueb, myself, and a few others were among them. But I think they know. People lack memory, but not to that extent. For us, for me, Bosnia-Herzegovina was like the Spanish Civil War. A war that was lost, like the war in Spain. But a war of such immense significance, of such huge symbolic value! I hope that the new generations know that. If they don’t, it will mean that amnesia, pure materialism, the absence of meaning, and nihilism have won out everywhere. I cannot imagine that. I can’t bring myself to believe that all those tears, all that spilled blood, all those vanished hopes—I can’t imagine that all that was in vain. But, like I say, we’ll see. Monday night is our rendez-vous with memory—and with honor. Looking for Europe in Sarajevo. The adventure began in Sarajevo. It ends—temporarily—in Sarajevo.

Has BH society done enough in terms of 'giving back' to its friends, and has it done enough to gain new friends? How can BiH give back? Could this small country survive without big friends all over the world?

- Bosnia has of course done enough. Speaking personally, I was decorated by Alija Izetbegović. Some years ago I was made an honorary citizen of the city. When Alija died, I was asked to deliver the eulogy, and I led the French delegation at his funeral. So, yes, what needed to be done was done. In any event, I ask for nothing more, nothing more than what has already been accorded me, which, in each instance, moved me to tears. But what I would like to say to you is this, above all. We internationals gave you a little. But you Bosnians gave a lot. You gave us a lot. You gave us an image of greatness. An example of resistance. An image, in miniature, of Europe. And that gift is of inestimable value. That is the meaning of the play, its deepest message. And that is why this play that I’ve been taking from city to city bears the secret name of Sarajevo. Or maybe it’s not so secret. The name Sarajevo shines at the heart of the play. It is that name that I have been singing, chanting, and wailing on the stages of Europe. Because, to the name of Sarajevo, to its inhabitants, all of Europe owes an infinite debt. I’m not saying that Sarajevo’s residents are living up to what I say of them. I’m not saying that they’re living up to what they were and what some of them still are. But that’s how it is. There is the ideal of the people of Sarajevo. And that ideal, I repeat, deserves infinite admiration. And infinite gratitude, as well. Before Sarajevo, I pray. And I ask forgiveness.

What would Europe look like if the right wing movement took over?

- Well, Europe would look like Bosnia today. In that sense, too, you would be in the vanguard. Because the borders of Europe would still be there. The institutions of Europe would still be there. The roof and the walls of the house would still be there. But instead of having democrats at the helm, instead of having democrats, whether of the left or the right, in parliament, we would all have the likes of Dodik. Take a good look at Dodik chairing the presidency of Bosnia-Herzegovina. That is exactly what Europe will look like if the illiberals come into power later in the month. And it’s precisely because of that resemblance, precisely because of Sarajevo’s vanguard role, that I am winding up this European tour in the city. I began the tour in Milan. I took it to Prague and Budapest, Rome and Lisbon, and many other cities. The formal closing will be in Paris, but the emotional closing is here in Sarajevo. And I’m doing it because Sarajevo today truly is the dark light shining in the night.